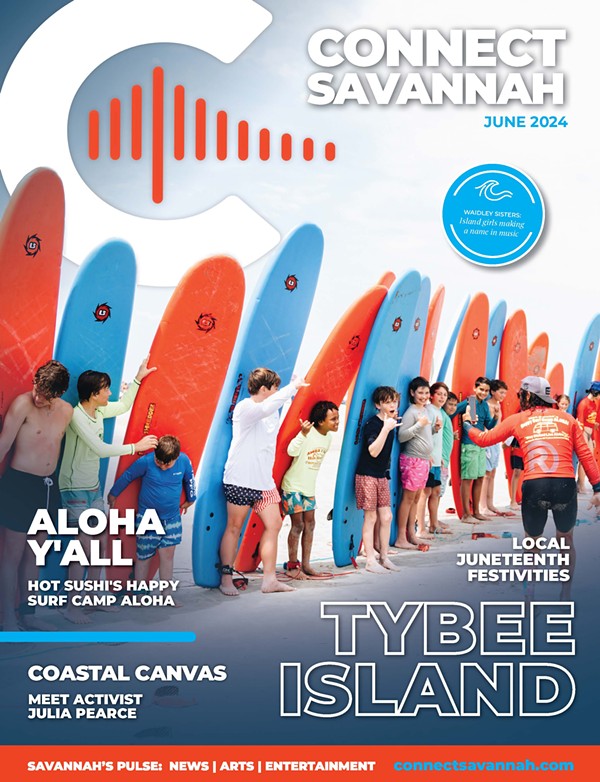

White surfboards ride the winds atop a bright orange VW bus bearing the license plate, Go Sushi. At the wheel, wind in his hair and rescue dog by his side, is Yamada, a Tokyo native turned Tybee Island surf instructor better known as Hot Sushi.

The van is more than mere conveyance. It is an unintentional billboard of sorts for Sushi’s brand, prompting at least one curious coffee-shop stranger to ask the lithe, long-haired, sun-kissed Sushi, “Dude, is that your van?”

It is the perfect chariot for Sushi, who finds joy and magic in most everything, from the mundane to the mystical.

For 11 weeks each summer, Sushi, founder of the aptly named Happy Surf Camp Aloha, is a Tybee Island fixture, doing far more than teaching his students about sun, sand, and surfing. He brings them into his world, inspiring them to embrace discipline, courage, commitment and well, delight.

“It’s the aloha spirit,” he said. “When the kids come in the morning, I want them to be lifted up. If you’re happy, do it. If you think you did something amazing, claim it. Don’t be shy. Scream.”Sushi has spent a lifetime doing just that. A literal world away from his upbringing in Tokyo, he has never forgotten his roots, his rise, or his role in the community. For Sushi, his camps are as much about humility and responsibility as they are about riding the waves.

“At the age of 61, I’m still rediscovering every day, to be humble and to be respectful,” Sushi said. “That’s the kind of thing I like to share with our future generations, so surfers who come to my surf camp, it’s not just about the sport. It’s about caring for the surroundings, ocean, people, equipment.”

It’s hard to believe Sushi did not take up surfing until he was in high school. As a child living in inland Tokyo, he didn’t even learn about surfing until he left elementary school. Soccer and baseball were the sports for inland kids.

“If you lived in the city, you had to have a ride to get to the beach,” he explained. “There’s no one waiting to take you out there, so there’s no chance. I lived three hours away, so no way.”

Instead, Sushi started skiing. He was just a toddler when his dad, a longtime snow skier, built a little mountainside lodge and introduced his two young sons to the slopes.

Sushi was 7 when he took up soccer and 17 when he began surfing. “I had to wait for somebody to get a license and a car,” he said of his late surfing start. “I had a one-year-older mentor who played soccer with us … the coolest kid in town. He started surfing much sooner and much earlier than us. He was so cool. And he started showing off the surfing magazines and the photos. We started trying to follow and begging him to take us. We had to wait our turn. So that was the way I started.”

Though he considers himself a student of the three esses (soccer, skiing, and surfing), it was skiing that first opened Sushi’s eyes to the world beyond Japan’s borders. Following in his father’s ski-clad footsteps, Sushi became a professional skier who started shredding the slopes of Europe at 18. The fact that he did not speak any language other than Japanese did not matter.

“When you discover the beauty of the sport, you don’t need language,” he said. “You have the same passion, the same interests. When I put my skis on, I was over the world. I didn’t need to speak; I just needed to ski to communicate.” That was not the case for surfing, at least not at first. Still new to the art of riding waves, Sushi and two other amateur surfers ventured to California in 1986, even though they knew little, if anything, about the language, the location, or the logistics.

They were influenced, Sushi says, by his older brother, who listened to US music, the imported surfing magazines they flipped through at the bookstore, and the Vans shoes they could not afford to buy.

“We would go to the shop, and we were just holding them, smelling the shoes, and I could smell California,” he said. “Seriously. Everything was the image of California back then. The T-shirts, the clothing. So, we decided we had to go to California.”

And they did. A vaudevillian journey ensued for Sushi, who did not realize the distance between Los Angeles and San Francisco and had to begrudgingly make his way via Greyhound from one city to the other to meet his friends.

“It was my bad,” he said. “I didn’t do any research, and I didn’t have many resources. It was so much effort to get there.”

But worth it.

“To me, surfing is more special,” Sushi said. “I could not get my own surfboard until I was 22. And then the surfboard didn’t come in one piece. It was so cheap and used, a broken board I had to repair. That’s why surfing is the most special thing compared to soccer and skiing, because there was some foundation with those already.”

Surfing, though, would have to wait.

When he returned from his three-week trip to California, Sushi filled his days working for a ski school in Japan and traveling to Europe to author stories about skiing. The promise of a new job at an exclusive and expansive hotel prompted Sushi to move from Japan to Guam in 1989. And thus started his life as a snow birder, spending winters teaching skiing in Japan and summers serving as a scuba diving, snorkeling, and wind surfing instructor in Guam.

“Surfing’s not huge there,” he said of the western Pacific Island. “Geographically, it’s surrounded by reef, so there’s no such thing as a sandy beach break. There isn’t much water, so you’re going to ride a 6-foot wave and if you fall, a pretty boo-boo.”

And that was a major no-no for Sushi’s other job: playing professional soccer for Guam’s national men’s team. Always humble, Sushi downplays the honor.

“I was only 30, so I was the oldest player on the team, but they didn’t have enough players anyway. I was good enough,” he said.

In the 1990s, Sushi got another opportunity: to house sit on the north shore of Oahu, Hawaii. And that’s when it happened: he rediscovered surfing.

“It was so different from the surfing I knew,” he said. “It was just a different ballgame. It was a different sport, the way they do it. It was an eye-opener, making me more humble and more respectful.”It was also where Sushi became an aloha advocate. He discovered and embraced the true meaning of the word, moving beyond mere greeting and farewell to its essence: love, affection, peace, compassion, mercy. To this day, Sushi lives by what he calls “the aloha spirit,” incorporating it into his camps and his lifestyle. “Aloha is not just a word,” he said. “It’s a way of life, a way to share our passion, to serve others and to learn the best way to live.”

After 12 years in Guam, Sushi moved to Savannah with his wife and their two kids, so they could be closer to her family. Once again, the US had surprises in store.

“Savannah, I thought there would be giraffes, rhinos,” he said. “It was a shock.”

So, too, was the water off the coast of Tybee, where he and his two children, a son and daughter, struggled to see through the murky depths. He did not realize surfing was an option until later. He was still spending six months a year as a sponsored skier, dividing his time between the island and the rest of the world.

“When my kids were old enough, I rediscovered Tybee Island,” he said. “I started to go there a little more often and started teaching my friends and my kids’ friends. I was just doing it for fun. And then someone said I should do this as my business. I started volunteering at the local YMCA surf camp, and then I decided I want to do it in my style. Don’t get me wrong, they have a fabulous program, but that wasn’t the way I wanted to run it. I just wanted to try it my way.”

That was roughly 10 years ago. And the rest, as they say, is history. Though he remains passionate about skiing and soccer, for Sushi, surfing is where the miracles—and the magic—happen.

“When all those children start to ride the wave, the whole vibe of the beach changes,” he said. “It is so magical. I have the privilege of seeing magic happen every day when I am there with them.”

Sushi finds magic in places others would not even think to look. Take, for example, when he was bitten by a shark during one of his surfing camps. Where others might see misery, Sushi, who still bears the physical and emotional scars from the ordeal, saw a miracle.

“I am still thankful that particular shark picked me,” he said.

The alternative, that the shark would pick one of the pint-sized students in his proximity, is too much for Sushi to think about. Three years later, he still struggles with those thoughts, though he was back in the ocean just two days after being whisked from the beach by ambulance.

“Ever since, I changed my perspective,” he said. “I feel lucky to be alive. So, if I need to spare my life for somebody, I would do it, especially younger generations.”

Even his students know their time with Sushi is about more than learning to surf.

“Every time I talk about it, even the little campers are like, it’s not just about the sport,” he recounts. “We do more than surfing. It’s about making people happy and healthy through the sport we all love. And I can get that result every time I take people out to the ocean water. At the end of the day, I get smiles and hugs. Even in such a short period of time, I witness children grow so much.

"I know it’s my business and career; however, it’s more than a job. “It’s a part of my life. I just get motivated to live because of that.”